Dow Theory, Cycles, News and Random Walk

According to Charles H. Dow, the primary trend of the market is the broad, all-engulfing "tide," which is interrupted by "waves," or secondary reactions and rallies. Movements of smaller size are the "ripples" on the waves. The latter are generally unimportant unless a line (defined as a sideways structure lasting at least three weeks and contained within a price range of five percent) is formed. The main tools of the theory are the Transportation Average (formerly the Rail Average) and the Industrial Average. The leading exponents of Dow's theory, William Peter Hamilton, Robert Rhea, Richard Russell and E. George Schaefer, rounded out Dow's theory but never altered its basic tenets.

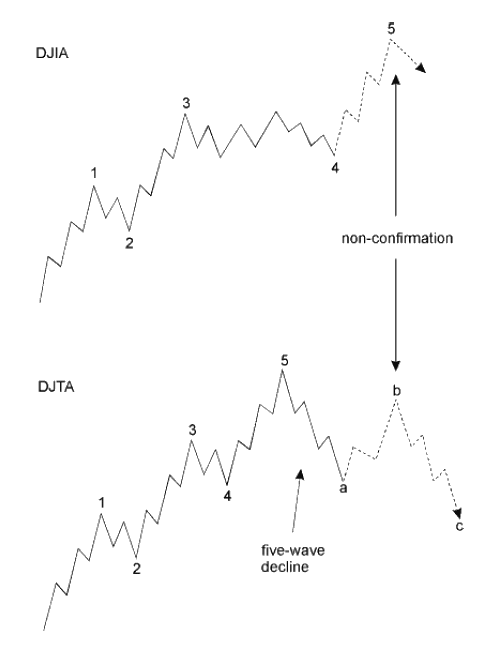

As Charles Dow once observed, stakes can be driven into the sands of the seashore as the waters ebb and flow to mark the direction of the tide in much the same way as charts are used to show how prices are moving. Out of experience came the fundamental Dow Theory tenet that since both averages are part of the same ocean, the tidal action of one average must move in unison with the other to be authentic. Thus, a movement to a new extreme in an established trend by one average alone is a new high or new low which is said to lack "confirmation" by the other average.

The Elliott Wave Principle has points in common with Dow Theory. During advancing impulse waves, the market should be a "healthy" one, with breadth and the other averages confirming the action. When corrective and ending waves are in progress, divergences, or non-confirmations, are likely. Dow's followers also recognized three psychological "phases" of a market advance. Naturally, since both methods describe reality, the descriptions of these phases are similar to the personalities of Elliott's waves 1, 3 and 5 as we outlined them in Lesson 14.

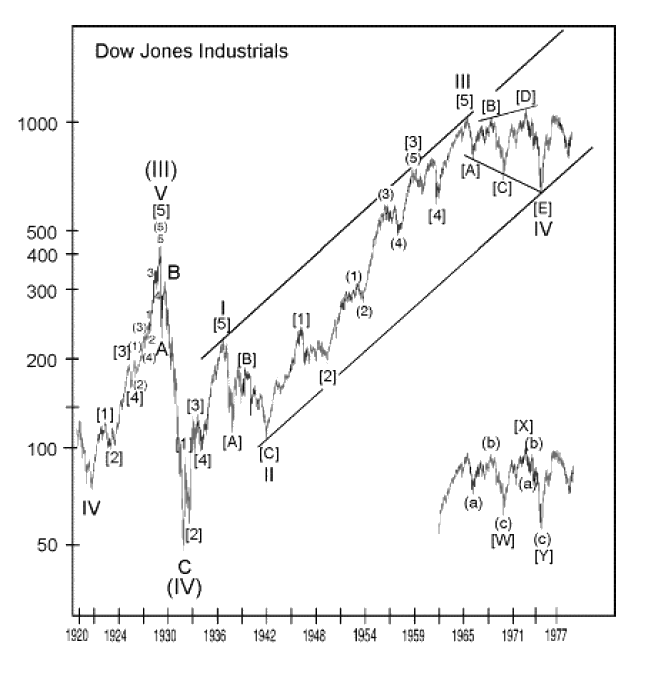

Figure 7-1

The Wave Principle validates much of Dow Theory, but of course Dow Theory does not validate the Wave Principle since Elliott's concept of wave action has a mathematical base, needs only one market average for interpretation, and unfolds according to a specific structure. Both approaches, however, are based on empirical observations and complement each other in theory and practice. Often, for instance, the Elliott count can forewarn the Dow Theorist of an upcoming non-confirmation. If, as Figure 7-1 shows, the Industrial Average has completed four waves of a primary swing and part of a fifth, while the Transportation Average is rallying in wave B of a zigzag correction, a non-confirmation is inevitable. In fact, this type of development has helped the authors more than once. As an example, in May 1977, when the Transportation Average was climbing to new highs, the preceding five-wave decline in the Industrials during January and February signaled loud and clear that any rally in that index would be doomed to create a non-confirmation.

On the other side of the coin, a Dow Theory non-confirmation can often alert the Elliott analyst to examine his count to see whether or not a reversal should be the expected event. Thus, knowledge of one approach can assist in the application of the other. Since Dow Theory is the grandfather of the Wave Principle, it deserves respect for its historical significance as well as its consistent record of performance over the years.

Cycles

The "cycle" approach to the stock market has become quite fashionable in recent years, coinciding with the publishing of several books on the subject. Such approaches have a great deal of validity, and in the hands of an artful analyst can be an excellent approach to market analysis. But in our opinion, while it can make money in the stock market as can many other technical tools, the "cycle" approach does not reflect the true essence of the law behind the progression of markets. In our opinion, the analyst could go on indefinitely in his attempt to verify fixed cycle periodicities, with negligible results. The Wave Principle reveals, as well it should, that the market reflects more the properties of a spiral than a circle, more the properties of nature than of a machine.

News

While most financial news writers explain market action by current events, there is seldom any worthwhile connection. Most days contain a plethora of both good and bad news, which is usually selectively scrutinized to come up with a plausible explanation for the movement of the market. In Nature's Law, Elliott commented on the value of news as follows:

At best, news is the tardy recognition of forces that have already been at work for some time and is startling only to those unaware of the trend. The futility in relying on anyone's ability to interpret the value of any single news item in terms of the stock market has long been recognized by experienced and successful investors. No single news item or series of developments can be regarded as the underlying cause of any sustained trend. In fact, over a long period of time the same events have had widely different effects because trend conditions were dissimilar. This statement can be verified by casual study of the 45 year record of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

During that period, kings have been assassinated, there have been wars, rumors of wars, booms, panics, bankruptcies, New Era, New Deal, "trust busting," and all sorts of historic and emotional developments. Yet all bull markets acted in the same way, and likewise all bear markets evinced similar characteristics that controlled and measured the response of the market to any type of news as well as the extent and proportions of the component segments of the trend as a whole. These characteristics can be appraised and used to forecast future action of the market, regardless of news.

There are times when something totally unexpected happens, such as earthquakes. Nevertheless, regardless of the degree of surprise, it seems safe to conclude that any such development is discounted very quickly and without reversing the indicated trend under way before the event. Those who regard news as the cause of market trends would probably have better luck gambling at race tracks than in relying on their ability to guess correctly the significance of outstanding news items. Therefore the only way to "see the forest clearly" is to take a position above the surrounding trees.

Elliott recognized that not news, but something else forms the patterns evident in the market. Generally speaking, the important analytical question is not the news per se, but the importance the market places or appears to place on the news. In periods of increasing optimism, the market's apparent reaction to an item of news is often different from what it would have been if the market were in a downtrend. It is easy to label the progression of Elliott waves on a historical price chart, but it is impossible to pick out, say, the occurrences of war, the most dramatic of human activities, on the basis of recorded stock market action. The psychology of the market in relation to the news, then, is sometimes useful, especially when the market acts contrary to what one would "normally" expect.

Experience suggests that the news tends to lag the market, yet follows exactly the same progression. During waves 1 and 2 of a bull market, the front page of the newspaper reports news that engenders fear and gloom. The fundamental situation generally seems the worst as wave 2 of the market's new advance bottoms out. Favorable fundamentals return in wave 3 and peak temporarily in the early part of wave 4. They return partway through wave 5, and like the technical aspects of wave 5, are less impressive than those present during wave 3 (see "Wave Personality" in Lesson 14). At the market's peak, the fundamental background remains rosy, or even improves, yet the market turns down, despite it. Negative fundamentals then begin to wax again after the correction is well under way. The news, or "fundamentals," then, are offset from the market temporally by a wave or two. This parallel progression of events is a sign of unity in human affairs and tends to confirm the Wave Principle as an integral part of the human experience.

Technicians argue, in an understandable attempt to account for the time lag, that the market "discounts the future," i.e., actually guesses correctly in advance changes in the social condition. This theory is initially enticing because in preceding social and political events, the market appears to sense changes before they occur. However, the idea that investors are clairvoyant is somewhat fanciful. It is almost certain that in fact people's emotional states and trends, as reflected by market prices, cause them to behave in ways that ultimately affect economic statistics and politics, i.e., produce "news." To sum up our view, then, the market, for our purposes, is the news.

Random Walk Theory

Random Walk theory has been developed by statisticians in the academic world. The theory holds that stock prices move at random and not in accord with predictable patterns of behavior. On this basis, stock market analysis is pointless as nothing can be gained from studying trends, patterns, or the inherent strength or weakness of individual securities.

Amateurs, no matter how successful they are in other fields, usually find it difficult to understand the strange, "unreasonable," sometimes drastic, seemingly random ways of the market. Academics are intelligent people, and to explain their own inability to predict market behavior, some of them simply assert that prediction is impossible. Many facts contradict this conclusion, and not all of them are at the abstract level. For instance, the mere existence of very successful professionals who make hundreds, or even thousands, of buy and sell decisions a year flatly disproves the Random Walk idea, as does the existence of portfolio managers and analysts who manage to pilot brilliant careers over a professional lifetime. Statistically speaking, these performances prove that the forces animating the market's progression are not random or due solely to chance. The market has a nature, and some people perceive enough about that nature to attain success. A very short term speculator who makes tens of decisions a week and makes money each week has accomplished something akin to tossing a coin fifty times in a row with the coin falling "heads" each time. David Bergamini, in Mathematics, stated,

Tossing a coin is an exercise in probability theory which everyone has tried. Calling either heads or tails is a fair bet because the chance of either result is one half. No one expects a coin to fall heads once in every two tosses, but in a large number of tosses, the results tend to even out. For a coin to fall heads fifty consecutive times would take a million men tossing coins ten times a minute for forty hours a week, and then it would only happen once every nine centuries.

An indication of how far the Random Walk theory is removed from reality is the chart of the Supercycle in Figure 5-3 from Lesson 27, reproduced below. Action on the NYSE does not create a formless jumble wandering without rhyme or reason. Hour after hour, day after day and year after year, the DJIA's price changes create a succession of waves dividing and subdividing into patterns that perfectly fit Elliott's basic tenets as he laid them out forty years ago. Thus, as the reader of this book may witness, the Elliott Wave Principle challenges the Random Walk theory at every turn.