Introducing Fibonacci

Historical and Mathematical Background of the Wave Principle

The Fibonacci (pronounced fib-eh-nah´-chee) sequence of numbers was discovered (actually rediscovered) by Leonardo Fibonacci da Pisa, a thirteenth century mathematician. We will outline the historical background of this amazing man and then discuss more fully the sequence (technically it is a sequence and not a series) of numbers that bears his name. When Elliott wrote Nature's Law, he referred specifically to the Fibonacci sequence as the mathematical basis for the Wave Principle. It is sufficient to state at this point that the stock market has a propensity to demonstrate a form that can be aligned with the form present in the Fibonacci sequence. (For a further discussion of the mathematics behind the Wave Principle, see "Mathematical Basis of Wave Theory," by Walter E. White, in New Classics Library's forthcoming book.)

In the early 1200s, Leonardo Fibonacci of Pisa, Italy published his famous Liber Abacci (Book of Calculation) which introduced to Europe one of the greatest mathematical discoveries of all time, namely the decimal system, including the positioning of zero as the first digit in the notation of the number scale. This system, which included the familiar symbols 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, became known as the Hindu-Arabic system, which is now universally used.

Under a true digital or place-value system, the actual value represented by any symbol placed in a row along with other symbols depends not only on its basic numerical value but also on its position in the row, i.e., 58 has a different value from 85. Though thousands of years earlier the Babylonians and Mayas of Central America separately had developed digital or place-value systems of numeration, their methods were awkward in other respects. For this reason, the Babylonian system, which had been the first to use zero and place values, was never carried forward into the mathematical systems of Greece, or even Rome, whose numeration comprised the seven symbols I, V, X, L, C, D, and M, with non-digital values assigned to those symbols. Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division in a system using these non-digital symbols is not an easy task, especially when large numbers are involved. Paradoxically, to overcome this problem, the Romans used the very ancient digital device known as the abacus. Because this instrument is digitally based and contains the zero principle, it functioned as a necessary supplement to the Roman computational system. Throughout the ages, bookkeepers and merchants depended on it to assist them in the mechanics of their tasks. Fibonacci, after expressing the basic principle of the abacus in Liber Abacci, started to use his new system during his travels. Through his efforts, the new system, with its easy method of calculation, was eventually transmitted to Europe. Gradually the old usage of Roman numerals was replaced with the Arabic numeral system. The introduction of the new system to Europe was the first important achievement in the field of mathematics since the fall of Rome over seven hundred years before. Fibonacci not only kept mathematics alive during the Middle Ages, but laid the foundation for great developments in the field of higher mathematics and the related fields of physics, astronomy and engineering.

Although the world later almost lost sight of Fibonacci, he was unquestionably a man of his time. His fame was such that Frederick II, a scientist and scholar in his own right, sought him out by arranging a visit to Pisa. Frederick II was Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the King of Sicily and Jerusalem, scion of two of the noblest families in Europe and Sicily, and the most powerful prince of his day. His ideas were those of an absolute monarch, and he surrounded himself with all the pomp of a Roman emperor.

The meeting between Fibonacci and Frederick II took place in 1225 A.D. and was an event of great importance to the town of Pisa. The Emperor rode at the head of a long procession of trumpeters, courtiers, knights, officials and a menagerie of animals. Some of the problems the Emperor placed before the famous mathematician are detailed in Liber Abacci. Fibonacci apparently solved the problems posed by the Emperor and forever more was welcome at the King's Court. When Fibonacci revised Liber Abacci in 1228 A.D., he dedicated the revised edition to Frederick II.

It is almost an understatement to say that Leonardo Fibonacci was the greatest mathematician of the Middle Ages. In all, he wrote three major mathematical works: the Liber Abacci, published in 1202 and revised in 1228, Practica Geometriae, published in 1220, and Liber Quadratorum. The admiring citizens of Pisa documented in 1240 A.D. that he was "a discreet and learned man," and very recently Joseph Gies, a senior editor of the Encyclopedia Britannica, stated that future scholars will in time "give Leonard of Pisa his due as one of the world's great intellectual pioneers." His works, after all these years, are only now being translated from Latin into English. For those interested, the book entitled Leonard of Pisa and the New Mathematics of the Middle Ages, by Joseph and Frances Gies, is an excellent treatise on the age of Fibonacci and his works.

Although he was the greatest mathematician of medieval times, Fibonacci's only monuments are a statue across the Arno River from the Leaning Tower and two streets which bear his name, one in Pisa and the other in Florence. It seems strange that so few visitors to the 179-foot marble Tower of Pisa have ever heard of Fibonacci or seen his statue. Fibonacci was a contemporary of Bonanna, the architect of the Tower, who started building in 1174 A.D. Both men made contributions to the world, but the one whose influence far exceeds the other's is almost unknown.

The Fibonacci Sequence

In Liber Abacci, a problem is posed that gives rise to the sequence of numbers 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, and so on to infinity, known today as the Fibonacci sequence. The problem is this:

How many pairs of rabbits placed in an enclosed area can be produced in a single year from one pair of rabbits if each pair gives birth to a new pair each month starting with the second month?

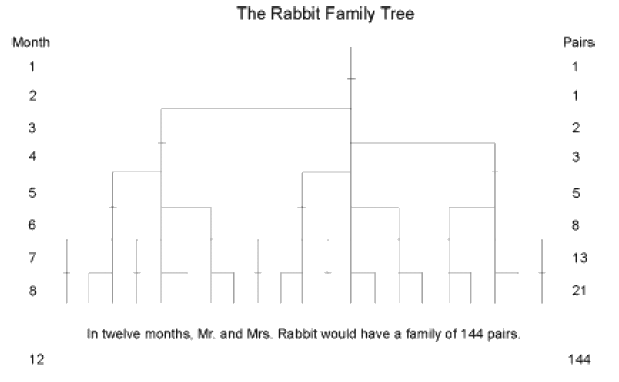

In arriving at the solution, we find that each pair, including the first pair, needs a month's time to mature, but once in production, begets a new pair each month. The number of pairs is the same at the beginning of each of the first two months, so the sequence is 1, 1. This first pair finally doubles its number during the second month, so that there are two pairs at the beginning of the third month. Of these, the older pair begets a third pair the following month so that at the beginning of the fourth month, the sequence expands 1, 1, 2, 3. Of these three, the two older pairs reproduce, but not the youngest pair, so the number of rabbit pairs expands to five. The next month, three pairs reproduce so the sequence expands to 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 and so forth. Figure 3-1 shows the Rabbit Family Tree with the family growing with logarithmic acceleration. Continue the sequence for a few years and the numbers become astronomical. In 100 months, for instance, we would have to contend with 354,224,848,179,261,915,075 pairs of rabbits. The Fibonacci sequence resulting from the rabbit problem has many interesting properties and reflects an almost constant relationship among its components.

Figure 3-1

The sum of any two adjacent numbers in the sequence forms the next higher number in the sequence viz., 1 plus 1 equals 2, 1 plus 2 equals 3, 2 plus 3 equals 5, 3 plus 5 equals 8, and so on to infinity.

The Golden Ratio

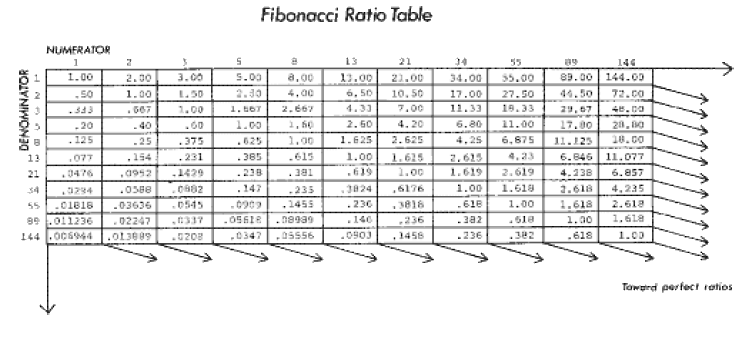

After the first several numbers in the sequence, the ratio of any number to the next higher is approximately .618 to 1 and to the next lower number approximately 1.618 to 1. The further along the sequence, the closer the ratio approaches phi (denoted f) which is an irrational number, .618034.... Between alternate numbers in the sequence, the ratio is approximately .382, whose inverse is 2.618. Refer to Figure 3-2 for a ratio table interlocking all Fibonacci numbers from 1 to 144.

Figure 3-2

Phi is the only number that when added to 1 yields its inverse: .618 + 1 = 1 ÷ .618. This alliance of the additive and the multiplicative produces the following sequence of equations:

.6182 = 1 - .618,

.6183 = .618 - .6182,

.6184 = .6182 - .6183,

.6185 = .6183 - .6184, etc.

or alternatively,

1.6182 = 1 + 1.618,

1.6183 = 1.618 + 1.6182,

1.6184 = 1.6182 + 1.6183,

1.6185 = 1.6183 + 1.6184, etc.

Some statements of the interrelated properties of these four main ratios can be listed as follows:

1) 1.618 - .618 = 1,

2) 1.618 x .618 = 1,

3) 1 - .618 = .382,

4) .618 x .618 = .382,

5) 2.618 - 1.618 = 1,

6) 2.618 x .382 = 1,

7) 2.618 x .618 = 1.618,

8) 1.618 x 1.618 = 2.618.

Besides 1 and 2, any Fibonacci number multiplied by four, when added to a selected Fibonacci number, gives another Fibo-nacci number, so that:

3 x 4 = 12; + 1 = 13,

5 x 4 = 20; + 1 = 21,

8 x 4 = 32; + 2 = 34,

13 x 4 = 52; + 3 = 55,

21 x 4 = 84; + 5 = 89, and so on.

As the new sequence progresses, a third sequence begins in those numbers that are added to the 4x multiple. This relationship is possible because the ratio between second alternate Fibonacci numbers is 4.236, where .236 is both its inverse and its difference from the number 4. This continuous seriesbuilding property is reflected at other multiples for the same reasons.

1.618 (or .618) is known as the Golden Ratio or Golden Mean. Its proportions are pleasing to the eye and an important phenomenon in music, art, architecture and biology. William Hoffer, writing for the December 1975 Smithsonian Magazine, said:

...the proportion of .618034 to 1 is the mathematical basis for the shape of playing cards and the Parthenon, sunflowers and snail shells, Greek vases and the spiral galaxies of outer space. The Greeks based much of their art and architecture upon this proportion. They called it "the golden mean."Fibonacci's abracadabric rabbits pop up in the most unexpected places. The numbers are unquestionably part of a mystical natural harmony that feels good, looks good and even sounds good. Music, for example, is based on the 8-note octave. On the piano this is represented by 8 white keys, 5 black ones — 13 in all. It is no accident that the musical harmony that seems to give the ear its greatest satisfaction is the major sixth. The note E vibrates at a ratio of .62500 to the note C. A mere .006966 away from the exact golden mean, the proportions of the major sixth set off good vibrations in the cochlea of the inner ear — an organ that just happens to be shaped in a logarithmic spiral.

The continual occurrence of Fibonacci numbers and the golden spiral in nature explains precisely why the proportion of .618034 to 1 is so pleasing in art. Man can see the image of life in art that is based on the golden mean.

Nature uses the Golden Ratio in its most intimate building blocks and in its most advanced patterns, in forms as minuscule as atomic structure, microtubules in the brain and DNA molecules to those as large as planetary orbits and galaxies. It is involved in such diverse phenomena as quasi crystal arrangements, planetary distances and periods, reflections of light beams on glass, the brain and nervous system, musical arrangement, and the structures of plants and animals. Science is rapidly demonstrating that there is indeed a basic proportional principle of nature. By the way, you are holding your mouse with your five appendages, all but one of which have three jointed parts, five digits at the end, and three jointed sections to each digit.